Isn't it fascinating and unsettling to note that the more we try to be independent, the more interdependent we find ourselves to be?

06 July, 2024

In defense of Maya

11 December, 2022

Glimpses of the subject

“We do not belong to this material world that science constructs for us. We are not in it; we are outside. We are only spectators. The reason why we believe that we are in it, that we belong to the picture, is that our bodies are in the picture. Our bodies belong to it.” --Erwin Schrodinger

~*~*~*~*~*

In the way Science is practiced today, and in Analytic Philosophy that underlies most scientific inquiry, the process of inquiry is predominantly objective. Much of scientific studies and Western philosophy (as practiced today) inquires about stuff that are "out there". Indeed, a study is considered scientific, only when the observer is separated from the system being observed, and the process of observation does not interfere with the functioning of the system.

Recently, I was watching a lecture on Analytic Philosophy, in which the professor defined philosophical inquiry as comprising of three major dimensions-- "what is out there?", "how do I know?", and "what do I do?" The first dimension comprises of different hermeneutic schools and different conceptual models of reality. The second dimension addresses issues of knowledge, cognition, epistemology, and so on. The third dimension addresses issues like imperatives, norms, morality, ethics, rational choice, etc.

In contrast to the above, one of the predominant questions addressed by Indian philosophical schools is "who am I?" Unlike Western thought that has predominantly focused on the object of inquiry , the focus in Indian schools has been predominantly on the subject or the inquirer.

It is not that the inquirer does not feature in Western thought. But the depths to which the inquirer has been inquired, is much more in Indian thought.

Most scientific models today require us to remove the inquirer from theories of reality. The inquirer needs to be a disinterested observer who does not interfere with the system being observed, and should not feature in the models of reality that is the outcome of the inquiry.

Such a requirement was found to be inadequate when scientific inquiry was focused on the very small and the very large-- quantum mechanics and the theory of relativity, respectively-- where it was seen that we cannot discount the observer in our models of reality. Similarly, in social sciences, there is often an argument that a dispassionate observer cannot understand underlying latent worldview and thoughts that drive observable patterns of behaviour of a population being observed, and a real sociological inquiry comes from a lived experience. It is only when we experience the pains, the joys, the insecurities, etc. of the population being observed, can we really understand why they act the way they do.

~*~*~*~*~*

Why is an inquiry into the inquirer important?

One of the biggest dreams of scientists, mathematicians and philosophers alike, has been to develop some form of "Grand Unified Theories" of reality. In Western thought, Albert Einstein, David Hilbert, and several others have attempted this immense feat, and have ultimately failed.

But once we realise that the inquirer is part of reality too, we see that we can never have any form of objective grand unified theory of reality-- without a theory of the inquirer itself!

The inquirer is so fundamental to our experience when we are inquiring about the world out there, that we often completely forget that it exists, and that its existence itself is a mystery! For example, other than on planet Earth, we do not have any evidence of an inquirer or an inquiry happening in any other planet in our solar system or in the known universe! (Of course, notable exceptions are the various satellites, rovers and other gadgets in different parts of the universe that are "inquiring" on our behalf).

Given that the inquirer is so unique an entity in the universe, it is but an imperative that any unified models of reality should necessarily also address and accommodate the inquirer into such models!

Once we start inquiring into the inquirer, we see that the usual physical models of reality are inadequate to model the inquirer. The inquirer or the subject, is not only involved in observation of reality, but is also an active, autonomous agent of change! Constructs involving intention, free will, knowledge, belief, reason, morality, ethics, purpose, etc. are all attributed to the inquirer and not the inquired. We cannot meaningfully talk about the "intention" of planet Saturn for sporting rings, nor the "morality" of Jupiter wanting to be the biggest planet in our solar system. But such statements are meaningful when we are talking about subjects.

~*~*~*~*~*

Indian philosophy has predominantly focused on characterising the inquirer rather than the inquired. There are several schools of thought and models about the inquirer-- each, a fascinating journey in itself.

One of the major questions that is addressed by Indian thought is to "locate" the locus of of the inquirer. When we say that "I am the inquirer" the question then asks, "Who am I?" or where is the locus of this "I" or self? Does the "I" refer to our body? Our mind? Our "ego" (whatever it means)? Our genetic signature? Or is it somewhere else?

The quest for the locus of "I" has been so elusive, that there are indeed several schools of thought (most notably, Buddhism) that assert that there is no entity called the self or "I" at all! But then, the concept of "I" is so centrally used in our conversations that it is hard to also accept that the core driver of our inquiry is just a void.

There is a story about a scientist arguing with Sri Ramakrishna-- a well known 19th century Advaita philosopher-- saying that he has conducted several experiments involving both body and mind, and is convinced that there is no entity called "self" or "I" anywhere. To this, Sri Ramakrishna replied, "Who is convinced that there is no entity called self?"

The 15th century Advaita philosopher Sage Vidyaranya wrote several books proposing different heuristics, to help the reader understand the problem of self. His treatise called the drg-drisyha viveka (or, the theory of the "seer" and the "seen") is based on the postulate that the subject cannot observe its own locus. Or, whatever that the subject can directly observe, cannot be the locus of the subject, since there is a locus that is doing the observing. For instance, our eyes can see everything else but itself. It can only see an image of itself in the mirror or in a photograph. But it cannot directly observe itself. Similarly, a finger cannot touch itself.

While the eyes cannot "see" themselves, we can become "aware" of our eyes in our inquiry, and question about its state. For instance, we can become aware that our eyes are irritating, relaxed, dry, etc. In this case, the eyes become the observed, and the locus of our inquiry shifts somewhere deeper within us. Hence, if the eye can be the object of inquiry, it cannot be the locus of our subject. Thus, we can now ask, who is inquiring about the eye? If we say that it is our mind that inquires and it is because of our mind that we exist (according to Descartes who said "Cogito. Ergo, sum"), we can see that the mind itself can become an object of our inquiry! The popular field of "mindfulness" is all about observing our mind and our thoughts as they come and go. So if the mind is not the fundamental inquirer, then who is it that is observing the mind?

The argument proceeds like that to reach a singularity. We can see that no matter what we think is our locus of inquiry that is part of our physical experience-- can easily become an object of our experience! We can observe our thoughts, our emotions, even our "ego" (we can inquire and understand ourselves as a person and our personality), we can inquire about our innate nature-- thus showing that none of this is the locus of our subject!

The Samkhya school of philosophy which is more than 4000 years old, posits a "simpliciter" entity (a fundamental entity that exists on its own, and not derived from something else), called the "Purusha" that is termed the fundamental inquirer. Physical reality comprising of all objects that can be inquired about, is called Prakriti. One of the axioms of Purusha is that the Purusha cannot observe itself-- it can only "realise" itself, but never observe itself directly. It is the Purusha that is the source of all subjective constructs like free-will, intention, norms, etc. According to Samkhya, the universe is said to be made up of infinite numbers of Purusha objects and an infinite number of Prakriti objects.

The infinite cardinality of Purusha objects are disputed by other philosophical schools, which point at certain contradictions that such a formulation creates. For instance, we discover "objective" mathematical truths independently, despite that mathematical processing is completely happening within our minds. Also, despite the large diversity in our population on earth, several linguists have noted remarkable similarities in which language is constructed across the world. This has given rise to theories like the "language instinct" that argues that our ability for language is not something that is imbibed-- but something that is innate!

This brings us to one of the predominant models of Indian philosophy-- called as the Vedantic school-- which argues that there is only one Purusha or subject in the universe! It is this one same subject that is inquiring through a multitude of channels, which appear as different inquirers in physical reality. The locus of all our inquiry is the same, universal consciousness. The world is not just one family-- we are all the same person!

There is another story of Sri Ramakrishna in this regard. Once, someone asked Sri Ramakrishna on what is the basis of ethics on which we can build a theory of how to treat others. Conventionally, we use several bases like reflection (treat others like how you would like to be treated), virtue (uphold certain virtues in the way you treat others, etc.) But, Sri Ramakrishna had a very different answer. He said, "remember that there are no others"!

~*~*~*~*~*

Even in the Vedantic approach to understanding the subject, there are several sub-schools of thought-- primarily based on whether the core inquirer and the channel used for inquiry (our physical beings) are different or the same. I have written about this debate in other articles, and will not dwell upon this argument here.

09 November, 2022

Practical dharma

One of the most misunderstood concepts these days is the idea of dharma (and other related terms like karma). Dharma is variously translated as "duty", "righteousness", "ethics", "divine law", and even "religion"-- all of which, are incorrect definitions.

Dharma is the most fundamental of the four "drivers" or purusharthas of human behaviour: dharma, artha, kama, and moksha. The most accurate translation I can give for these terms respectively, are: sustainability, capability, agency, and liberation.

The term dharma comes from the root dhrt- which means something that sustains or prevails. Dharma refers to the property of a system of being, that remains invariant through the life cycle of the system. Dharma is what gives us our resilience to prevail across varying, adverse conditions and not be consumed by causal forces.

Dharma is not just a property of "living" beings-- it is a characteristic of all systems of being. The field of statistical mechanics in physics uses a postulate very centrally in its inquiry, which says that, every bounded system has one or more "stable" states which represent low energy or low stress states in its neighbourhood, into which, it settles down, when left alone. For instance, electrons in an atom settle down into specific orbits. If we excite an electron with some energy, it moves to a higher orbit-- but also becomes unstable. It would quickly discard the excess energy and come back to its stable state of being.

As complex living beings, these stable states of being are what constitutes our dharma. The principle of dharma holds whether we are talking about human societies, or the formation of crystals, or states of matter, or the climate, or the solar system, etc.

One of the tests I use to see if someone has understood the concept of dharma, is to ask them whether dharma exists as of now, on Jupiter or Pluto. If their understanding of dharma is only in social terms like duty or religion, they would say that dharma is not applicable on Pluto.

The most frustrating error of course, is to equate dharma with religion. Recently, I was listening to a talk where the speaker clarified the difference. Religion (or "faith" as understood in the dominant Western narrative today), is something personal and subjective, while dharma is an objective entity. The speaker gave an analogy of toothbrush and toothpaste. While we can share a tube of toothpaste, our toothbrush is personal. Dharma is something that is shared and depends on all of us, while religion or faith, is personal.

Dharma is not righteousness either. But protecting and upholding dharma helps in righteousness and civility to prevail. Dharma is not our duty as well. But protecting and upholding dharma helps us in performing our duties. Dharma is not ethics either. But protecting and upholding dharma helps empower ethical practices.

So how do we protect and uphold dharma? To do so, we need to understand the system of being that we are inquiring about and the environment (Vidhi) in which it is operating. As individuals, we are a system of being ourselves; and our family, work, society and even the physical environment around us represents the Vidhi in which we operate. Similarly, an institution could be the system of being whose dharma we are interested in, and its Vidhi represents the economic, cultural, social and physical environment in which it operates.

We need to then understand what is the set of invariant properties that characterise our system of being. What is it about us that remains constant across time and the various interactions that we perform? Similarly, for institutions, we ask what is it that needs to prevail, that makes the institution what it is.

Once we understand this, we then need to understand the "game" of interaction between the system and its Vidhi. Our Vidhi places lots of demands on us, for which we need to provide our best response.

A being operating in its Vidhi (under certain conditions) is guaranteed to have at least one state of equilibrium. This can actually be proven mathematically! The state of equilibrium represents the "mutual best response" function-- meaning, this is the best that the being can do given the demands of its Vidhi, and this is also the best that the Vidhi can demand, given how the being is operating.

Let us call the state of dharma of the being as 'd' and the state of equilibrium with the Vidhi as 'e'. The difference between 'd' and 'e' is our existential stress-- it is the difference between what sustains us and what is demanded of us. This formulation of existential stress remains the same, regardless of whether we are talking about individuals or institutions or communities or families or countries.

To uphold our dharma, we can adopt various strategies. We can improve our capabilities (artha) to find a different stable state of being which is closer to 'e'. Or we can change our Vidhi to find a different environment whose equilibrium state 'e' is closer to our state of sustainability 'd'. Or we could change the "game" or the nature of our interaction with our Vidhi so that it forms a game whose equilibrium state 'e' is closer to our 'd'.

All these are very different from doing our duties, or complying with orders, or upholding righteousness. We can do our duties or uphold righteousness these only after we can uphold our dharma in our Vidhi.

26 October, 2022

Integral Advaita of Swami Vivekananda

In some of my previous posts addressing differences between dualism and non-dualism and the idea of Maya, I had been addressing what I believe, to be the core dilemma that has characterised Indian thought over millennia.

One of the core characteristics of Indian philosophy based on the Vedas and Upanishads is that, unlike Western philosophy that focuses on objects and the universe external to the inquirer, the Upanishads start by focusing on the inquirer itself. This leads to some deep insights and theories about concepts like consciousness, awareness, and self.

A primary contention of Indian schools of thought is the simpliciter nature of consciousness. That is, it argues that the core of what forms our consciousness, exists by itself-- and is not a consequence of material interactions. Hence, our consciousness does not "emerge" from our brain cells, but rather, our brain cells "tune in" to consciousness that already exists in the universe. In this sense, we never "invent" anything in our minds-- we only discover insights.

The core debates of Indian thought, comes from trying to reconcile between material reality and the simpliciter consciousness. Material reality is considered as a "mould" through which, consciousness manifests and expresses itself in the material world. But, what is the source and basis of this material reality?

The Samkhya school argues that material reality is as real and as simpliciter as consciousness. It argues that the universe is inherently a dualism-- comprising of two realms called Prakriti and Purusha corresponding to the material reality and consciousness. Prakriti functions on the basis of physical laws and causality, while Purusha uses Prakriti as a mould for its manifestation and expression. According to Samkhya, there are infinitely many instances of Prakriti and Purusha pairs.

Other schools of thought, however, argue that an infinite number of Purusha instances leave major questions open-- for instance, what is the source of all these infinite instances, and is there one source or infinitely many sources for these infinite pairs, and so on. Based on such arguments, they contend that the Purusha (also variously called Brahman, Paramatma, Sakshi, or simply "that which is") is unitary. Hence, the universe is simply the one global consciousness, manifesting itself through potentially infinite instances of Prakriti.

The unification of consciousness, still leaves open, the question of Prakriti or material reality. Is there just one material universe, or are we in a material multiverse? And what is the source of this universal duality?

The non-dual schools of thought contend that all forms of duality simply leave open questions, and therefore, all the duality that we see-- including the duality of Prakriti and Purusha-- is only apparent duality. The universe is essentially just one, all permeating reality, which is the only entity there is.

Material reality or Prakriti is argued as being created by this universal consciousness and not the other way around. The material reality we see, is called Maya (often incorrectly translated as "illusion"). Our material sense of self-- namely the ego (which is also called jiva) is manifested in Maya, and sees the multitude nature of material reality. But an awakened self-- the non-dualists argue-- realises that it is nothing but the only thing there is-- Brahman. The core idea of non-dual philosophy is captured by this statement: Brahma satyam, jagat mithyam, jiva Brahmaivanapara. (Brahman alone is real, the material reality is ephemeral, and the ego is none other than Brahman)

The non-dual argument is the core philosophy of the Upanishads, which give several arguments to drive home this point. The non-dual argument also gave rise to several modes of inquiry that asks how does the existential self come to realise itself as Brahman? The concept of harmonising between our existential agent (ego) and the universal consciousness, is called Yoga. Several different pathways for Yoga are also proposed-- which include the paths of jnana (knowledge), bhakti (devotion), karma (action), shrama (effort), and so on.

The idea of non-dual reality however, was criticised by several social reformers at different points in history, corresponding to times when the society built on such a philosophy had run its course and started to degenerate. One of the core criticisms of philosophers like Buddha and Mahavira from the second and third century BCE, and later philosophers like Madhwa from the 15th century CE, focused on the "dismissive" nature of non-duality towards issues of material reality. Human problems like suffering, injustice, disease, etc. were all part of Maya, and hence considered ephemeral (and therefore unimportant to address).

But, it is important to note that none of the non-dualist philosophers themselves have ever argued that issues of material reality are unimportant. One of the most well known non-dualist Adi Shankara, from the 10th century CE, was known to be very dynamic in reviving Vedantic thought all over India and reforming society from degeneration in those days. Before his untimely death at the age of 34, he had already travelled across India on foot-- twice, and setup several centres of learning from Kashmir in the north, to Kanchi in the south. He had taken on several well-known philosophers from those days and defeated them in extensive debates, and urged them towards reforms.

While the philosophers themselves were anything but apathetic towards material reality, the argument that all aspects of material reality are part of Maya, does not provide a strong implication to help understand how to address existential issues.

Dualists like Madhwacharya, criticised the core philosophy of Jiva Brahmaivanapara (or the ego is none other than the Brahman), and instead argued that the jiva is completely contained within existential reality or Prakriti. It is too pretentious for our ego to believe that we are the entire universe-- all that our ego can do is to facilitate the universal consciousness to manifest through us, as best as possible. This line of argument, is also strongly entrenched in the Bhakti movement that advocated love, devotion, and surrender to the divine as a means of liberation.

More modern philosophers like Swami Vivekananda who rose to prominence during the Indian freedom struggle against British colonial rule, have argued that too much of an emphasis on Bhakti, leading to a perennial sense of surrender and submission makes us too obsequious, and impedes our ability for ownership. Ownership of larger issues-- like the safety, welfare and well-being of our family, community and country, are important pre-requisite to help sustain all forms of philosophical inquiry-- be it non-dual or dual.

Swami Vivekananda was a non-dual philosopher at his core. But he also combined his non-dual philosophy with several forms of social advocacy and reform-- including development of a scientific temper in the population, community welfare and service, focus on courage and bravery, development of patriotism, ownership and participation in issues relating to the country, and so on. Swami Vivekananda's social reforms have played critical roles in shaping the rise of post-colonial India. He had set up several institutions for both mainstream and spiritual education. He also played critical roles in the establishment of major scientific establishments like the Indian Institute of Science.

Vivekananda's approach to non-dual Vedanta is now called "Integral Advaita" in that, it strives to integrate seemingly breakaway schools of philosophy back into the core non-dual approach that has characterised Indian thought since thousands of years.

Here is a good introduction to Integral Advaita, by Swami Medhananda:

02 October, 2022

Dynamics of identity in Indian thought

One of the core tenets of Indian philosophy is that the only thing that is real is this all-pervading substratum that is variously called the universal consciousness, Brahman, universal Self, etc.

One of the primary points of difference between Indian thought and Western science, is the nature of consciousness. As mentioned in some of my earlier posts, in Indian thought, we are said to not "have" consciousness, but "reflect" consciousness. In contrast, in Western science, consciousness is considered as a material outcome, or an emergent characteristic of interacting brain cells.

In Indian thought, all material existence only reflects consciousness-- much like how all solid objects reflect sunlight. But sentient beings not only reflect the universal consciousness, but can also create an "image" of this universal consciousness-- the all pervading substratum-- to different levels of detail. This is somewhat like how few surfaces, like glass, mirror, polished steel, or water, not only reflect sunlight, but also form an image of the sun.

The sentience we attribute to ourselves, Indian thought says, is just a reflection of the universal consciousness. Whatever is illuminated by the reflection is essentially the universal consciousness or Brahman, affecting existence through us.

It is not that, such a theory was completely adopted in Indian thought. Indian philosophy also has a school of philosophy that is based on the material basis of reality-- much like modern science. These were called the nastika or the heterodox school of philosophy, of which the Caravakas are the most prominent. However, the nastikas have not found much support among other schools of Indian thought, all of which agree with the model of the all-pervasive universal consciousness. These were called the astikas or the orthodox school.

The vast differences between the different astika schools of philosophies lie in the way they argue about where our sense of self or the "I" that makes up who we are, exist. Almost all astikas (except perhaps the Samkhya school of thought) agree that the universal consciousness that we all individually reflect, is just one. This is somewhat like how we can see an image of the sun in several bowls of water placed outside. It does not mean that each bowl of water has its own sun-- the images of the sun in each bowl, are of the same sun. While each image in each bowl may end up reflecting different parts of each of the bowls, it is not the individual images that is illuminating the bowls-- but the one sun that is reflected in all of them.

Imagine now that each image of the sun in each bowl, thinks of itself as a separate individual-- separate from other suns in other bowls. This individuality we ascribe to ourselves is our "existential self" or ego, or what is called "jiva" or "atma" in Indian thought.

The different orthodox schools of Indian thought, argue about the nature of our existential self and its relationship with the universal self.

The Advaita school of thought argues that there is nothing else other than the universal self, and hence, there is nothing called an existential self. Our existential self is just Brahman entangled within Brahman to create a small echo chamber that appears as our existential self, and which primarily reflects Brahman. "Jiva Brahmaivanapara!" or "The jiva is none other than Brahman!" it argues.

According to Advaita, the only reason that we don't know that we are Brahman is due to this entanglement (called Maya) created by Brahman in which we exist. Once we realise this knowledge, it paves the way to understand our true nature.

A lot of other schools differ from Advaita in this regard. Some of them argue that the Advaitic argument is almost nihilistic, as it dismisses all forms of existential issues like ethics, morality, duty, etc. all to Maya, and calls them all unreal.

One of the biggest detractors of Advaita philosophy is the Dvaita philosophy, that argues for a dual nature of reality. One of the earliest dualists are the Samkhya philosophers who argue that reality is made of two realms called the "Purusha" and "Prakriti" or "Reality" and "Existence". Both Purusha and Prakriti exist in their own right (called "simpliciter" in Western philosophy). While Prakriti is the energy or force driven by causality, Purusha is the substratum that forms the contours of reality. Prakriti can exist only as long as its dynamics are consistent with Purusha, and collapses otherwise.

Samkhya argues that there are infinitely many Purusha and Prakriti duals that make up reality-- a claim that has been refuted by many later philosophers. The primary lacuna in this argument is that, if there are several Purushas, who determines the substratum of reality between their interactions?

Other dualists, like Madhvacharya who propounded the Dvaita school of thought, argue that while reality (Purusha, Brahman, universal consciousness) is one, there exist infinitely many jivas (existential self). The primary element of Dvaita philosophy is "bheda" or "boundary". Dvaita argues for boundaries that separate jiva and Brahman, jiva and jiva (i.e. any two existential selves), and jiva and jagat (non-sentient existence). They are all different, and all have a unique existence-- it argues.

Analytic Philosophy of Western thought (of which Bertrand Russell was a major proponent), developed in the late 19th and early 20th century, comes very close to such an argument. It argues that every concept and matter is "simpliciter" or has an existence of its own, independent of its relationships with any other entity.

According to the dualists, we are not Brahman, but jiva-- or the existential self. The existential self can never be the universal self, much like the glass reflecting the sun can never be the sun. The existential self can however, polish and enrich itself to reflect the universal self much better. This process or struggle by which jiva strives to enrich itself to better reflect Brahman, is called Sadhana.

The phenomenon of the jiva performing Sadhana to finally "join" or "harmonise" with the universal self, is called "Yoga" (yeah, somewhat different from what this term means today).

There are different ways in which this Sadhana is performed, which are also called margas or pathways. The bhakti marga for instance, advocates devotion or commitment to a cause or idea by the existential self, as a means for getting better and better at something, and end up eventually reflecting one aspect of the universal self by way of its superlative expertise.

While the concept of bhakti itself dates back to the Vedic times-- almost 5000 years ago, and primarily meant devotion and commitment, a much more recent phenomenon called the bhakti movement that began in the 12th century CE and lasted for a few centuries, and which had syncretic relationships with Sufi mysticism, also advocated surrender and submission to the divine, as part of its Sadhana. This form of bhakti involves us as the existential self, establishing a child-parent relationship with the divine or the universal self.

All this while, the Advaita school does not agree with the contention that just because it calls existential self as part of Maya and impermanent, it is nihilistic in its arguments. Quite the contrary-- it argues. According to Advaita, what we need is not Sadhana, but the shedding of Avidya (non-knowledge or delusion) that holds us in bondage. As long as we are deluded into believing that we are the bounded existential self, and keep longing for the divine, we continue to be trapped in our bondage-- it argues.

Rather than a child-parent relationship between our existential self and the universal self, we need to have a parent-child relationship, it argues. We need to identify not with the existential self, but realise ourselves as the universal self, and then interact with our existential self, as if a parent is interacting with their child. The existential self is a result of entanglement-- it is bounded and unwise, but has a lot of raw energy. Knowing ourselves as the universal self, we need to help the jiva calm down from its existential angst and use its energy wisely, to reflect the universal self.

This kind of an argument has its parallels in Western thought that came much later. For instance, modern psychotherapy has a concept called "reparenting" that involves talking to our emotional selves as if it were a child, and bring it up in a way that we are the parent to ourselves, whom we never had, while growing up. Similarly, the cognitive scientist Johnathan Haidt has this model called "The elephant and the rider" that explains the relationship between our rational self that can be wise but weak in terms of raw energy, and the emotional self that is impulsive and full of existential angst, but very strong in terms of raw energy.

*~*~*~*~*~*

The fascinating thing with Indian thought is that, no matter how we wish to see the world, there is a rich and well-developed philosophical school of thought in that direction, that accommodates us. Given my childhood trauma, and my issues with authority figures, the notion of bhakti-- especially practices that involve surrender and submission-- had not appealed to me at all. I would strongly advocate objectivity in our interaction, whenever elders and authority figures trained their guns at their perceived "lack of humility" from my part. Reading our recent history and our struggles with foreign oppression and colonialism, made the idea of surrender and submission even more abhorrent. "How can we advocate something, that kept us enslaved for so many centuries?" I have argued many times.

For someone who was pained by the arbitrariness of authority and searching for freedom, Indian philosophy offered me Advaita-- that is based on logic and argumentation, to realise the universal nature of our existence. (The argument is pretty simple actually-- based on reasoning about the subject and object in any inquiry. But explaining this is beyond the scope of this post).

But having understood and imbibed Advaita, my outlook towards bhakti has also changed considerably! I no longer view surrender and submission as abhorrent-- but only as sentiments of longing by jivas who are entangled in their existential contexts. They are like children longing for salvation from their parent-- not realising that the answers that they seek in their surrender to the divine, are essentially to be found within themselves.

This is summarised by a board with a saying, which I found in the Sannidhi of Sri Raghavendra Swami (a highly acclaimed Dvaita philosopher) in Mantralayam: "Don't come to me expecting me to solve your problems-- instead, come to me to find me within yourselves."

28 March, 2022

Vedanta and machine consciousness

In a previous post, we had seen how the concept of consciousness differs between Indian philosophy rooted in the Vedas, and modern Western scientific models. Specifically, while Western science models consciousness as an attribute of a being, Indian philosophy models consciousness as the fundamental substance of the universe. Beings are considered to reflect this universal consciousness to various degrees, and not have consciousness themselves.

To explain this, we had given the analogy of the space just outside of the Sun that appears dark, but which is full of light. We cannot see this light, unless there is something to reflect it.

In this post, we will delve into the notion of consciousness further. If all we do is reflect universal consciousness, then what makes us appear conscious, and say a stone, appear unconscious? What kind of beings reflect this universal consciousness, and what beings don't?

Indian philosophy has an answer to this too. Consider objects around us in broad daylight. All of them reflect sunlight-- much in the same way that all beings (living or non-living) reflect consciousness. However, on a few surfaces like glass, water, polished metal etc. we not only can see sunlight reflected off them, but also an image of the Sun itself-- the source of the light.

This metaphor helps to explain sentience and non-sentience in systems of being. Sentient beings not only reflect consciousness, they also can-- to different extents-- form an image of the universe itself!

By this model, when we consciously create something, we are actually channelizing or using the universal consciousness into some creation of ours-- somewhat like the image below. Our creation may collapse eventually, but the universal consciousness remains eternally.

Beings are said to comprise of two kinds of "bodies"-- called the sthula sharira and the sookshma sharira translating roughly to "material body" and "subtle body". In my book called The Theory of Being. I had called this the two "realms" of existence of any being in this universe-- the material realm and the information realm.

The material body is our physical body that exists in the physical universe. The "subtle body" is variously (and in my opinion, incorrectly) equated with terms like "soul" or "spirit" represents all the information related processing that is part of who we are.

The subtle body in turn, is said to comprise of three components: pranamaya kosa, manomaya kosa, and vijnanamaya kosa. The pranamaya kosa represents all forms of information constructs that keep our material bodies alive. They contain our emotional dispositions, defence mechanisms, fight or flight responses, internal communication protocols for signalling danger, hunger, pain, etc. The manomaya kosa represents our "mind" that implements our "sense of self" and ego. This aspect of the subtle body encodes a representation of our self image, who we think we are, all the persona of ourselves that we project in social settings, what we desire, what we despise, etc. The vijnanamaya kosa represents our objective knowledge about the universe. It contains our models of reality around us, general knowledge constructs, episodic memory, etc.

Sentient beings that can reflect an image of consciousness, rather than just scatter consciousness, are said to have highly evolved subtle bodies. A subtle body is (in mechanistic terms) essentially a large body of software that can keep a material body alive, build models of the external world and manage knowledge about it, and have a "sense of self".

Of these, we already can build machines that can do the first two operations very well. We can build robots that are adaptive and self-configuring in order to keep themselves going. We also can build AI that can build semantic models based on data, which it can then use to perform a variety of intelligent tasks.

The only missing element in building a full-fledged subtle body for our machines, seems to be a "sense of self". Hmmm.. What does it mean for machines to have a sense of self? What exactly do we mean by a "sense of self"?

A few weeks ago, I had given a talk on this very question, which may be found here:

Hope you enjoy the presentation!

08 March, 2022

Vedanta and Genetics

Indian thought has been greatly shaped by the philosophy of Vedas that are estimated to have developed over several millennia, beginning as early as 22000 BCE.

The Vedas presented a deep, abstract model of reality, that has in turn shaped collective worldview and notions of religion, ethics, morality and science. The civilisation formed under the influence of this philosophy (even those subcultures that rejected this philosophy) was vibrant and diverse, with different schools of interpretations appearing throughout history. There were also several periods of stagnation and degeneration, followed by rejuvenation of this philosophy by one or more social reformers, including Buddha, Mahavira, Adi Shankara, and so on.

In this post, we address one such issue that has created deep roots in Indian thought, and which is in dire need for reforms.

*~*~*~*~*

The core inquiry of Vedic thought focuses on the nature of our self. The Upanishads, which are considered the essence of the Vedas, have several models and analogies to help us understand who is this "I" when we refer to ourselves.

We can see that we as the observer or the subject, is separate from the observed, or the object. And when we start observing ourselves, just about everything we thought represented us, becomes an object of our observation-- meaning that none of these define our "self." We can separate "us" from our thoughts, our emotions, our innate nature, our desires, our delusions, and so on. Our self is none of these. We are not our thoughts, we are not our emotions, we are not our innate nature, since we can observe all of them objectively.

The only entity we cannot observe is our "self" itself. This core entity which is our true self, is called the "witness" or Sakshi, who observes everything. We cannot observe our witness-- if we are observing our witness, then who is the witness witnessing it? We can only "become" our witness.

The sense of self that we normally project as part of our daily lives is known as the "jivatma" or "ahamkara", which is somewhat equivalent to the concept of ego in Freudian thought. The only way our self observes itself is by looking at its reflection, which is the ahamkara. It is somewhat like how the only way our eyes can see itself is by looking at its reflection in a mirror.

What is the medium that is giving this reflection? This is postulated as our mind. Our mind is the medium which hosts the reflection of our true selves, which appears in the form of our ego.

The reflecting surface may be imperfect. A mirror may be stained, dusty or even broken. The reflecting surface affects the reflection. Our reflection in the mirror may appear dull or stained or broken-- but it is only our reflection. Our true self, which lies beyond the mirror is unaffected by all the thoughts, emotions and innate nature that shape the medium of our mind.

*~*~*~*~*

A major debate among Vedic philosophers has been to model the association between our real self and the reflected self and its medium. Is our real self completely independent of our manifested self? Just like how we are completely independent of any mirror that reflects us? Or is there some "binding" that binds our real self to the mind/body medium that is reflecting us? Is there some reason why our real self is strongly associated with-- or even "trapped" in-- the mind-body complex that is reflecting it?

In the 10th century CE, Vedic thought went through one more round of major rejuvenation, by the works of Adi Shankara from present day Kerala. In his quest to revive Vedic philosophy, Adi Shankara wrote detailed commentaries on 10 Upanishads that are now called the "principal" Upanishads, and formulated his own school of thought called Advaita Vedanta.

According to Advaita which literally means "non-dualism", everything in the universe is made of the universal consciousness that is called Brahman. That includes our witness, our mind, our ego, our body-- everything. There is hence no difference between us and the mirror. Imagine that our hands were to be a reflecting surface, and we put up our hands to get a reflection of ourselves. We may not be our reflection in our hand-- but we are very much the hand and the reflection as well!

Other philosophers like Madhvacharya disagreed with this interpretation by arguing that it seems to border on nihilism. If everything is the universal consciousness Brahman, and there is no semantics associated with our existential self, then why do we have notions like ethics, morality, duty, principles, and so on? A similar argument was also given more than 1500 years before Madhvacharya, by Siddharta Gautama (Buddha) who was disillusioned with a puritanical notion of "everything is Brahman" leading to nihilistic thought.

One of the theories that came about to explain the relationship between our true self and the existential self, is the concept of prarabdha karma. The term karma means "action" but thanks to this theory, karma has now come to mean "retribution" in popular thought.

The idea of prarabdha karma is that our existential self goes through several cycles of births and deaths, and the karma (actions) it performs out of its own free will in one life, has consequences and gains some baggage, which becomes our prarabdha (starting) karma as we begin our next life.

The idea here had been to provide a sense of accountability for people acting out their worldly desires, by saying that their actions will have consequences and they will need to own up their actions. This is somewhat similar to the notion of judgement day in Abrahamic religions. But in contrast to being "judged" by a third party, we get to suffer or enjoy the consequences of our karma in our next life.

While this looks like a neat theory and strategy for bringing about accountability, this theory also has a dark side. The idea of prarabdha karma and "next life" can also ironically make people very apathetic towards one another. If someone were to be born with some birth defect, then not only they have to live with their birth defect, but they are also insinuated by others, that they must have done something bad in their previous life, and so are suffering in this life! Not only do they not get support and empathy from others, they have to suffer an unknown guilt all their life!!

And of course, this leads to feudal hierarchies like "lower" births and "higher" births based on what one had done in their previous life.

*~*~*~*~*

The above notion is in serious need of reform in today's world. Firstly, there is no evidence for any past life of any kind. Indeed, if we only go from life to life, then the total amount of living beings on earth needs to be constant! If everyone is born with a baggage from their previous life, how come we have more people today than there were a century ago?

In fact, we have a much better explanation for where our innate nature comes from. It comes from our genes!

If we have to understand our innate nature, we don't have to look for some non-existent "past life." We just have to look at our genetic ancestry. We know for a fact that, intense experiences like desperation and trauma encountered by one generation, makes its genetic imprint on the next generation. The next generation is innately equipped with defences and barriers to avoid what the previous generations went through.

Social accountability is an important question-- but that it should not be confounded with our innate genetic nature. There is no reason to equate our innate nature with some form of undesirable actions we are said to have performed in some fictitious past life.

It is time we replaced prarabdha karma with prarabhda guna (initial characteristics) and separate it from the actions we do in this life. I have written separately about karmaphala or the consequences of our actions. It is an profound theory in itself, that can be understood better when we understand the dynamics of complex systems. The consequences of our actions have nothing to do with our innate nature, which is just an accident of birth.

16 November, 2021

Reviving Bharatiya Vigyan - 1: Getting the hermeneutics right

सुखम समग्रम विज्ञाने विमलेच प्रतिष्ठितं

Sukham samagram vijnane vimalecha pratishtitham

"All happiness is rooted in good science," says the Charaka Samhita-- the definitive treatise on Ayurveda, dating back to 8th century BCE. This belies the widely believed notion that science and "scientific temper" came to India from the West.

Every form of scientific practice, rests upon an underlying hermeneutics-- or a way of thinking. The hermeneutics of current day scientific inquiry is greatly influenced by the industrial revolution, which in turn was fuelled by colonial expansion of European powers. I've called this form of inquiry as "machine hermeneutics" and also sometimes called the "clockwork model," where the universe is considered to be a giant, impersonal automaton, driven solely by causality, and indifferent to our existence.

Hermeneutics affect how we interpret our observations and what models we build. As the physicist Werner Heisenberg once said, "What we observe is not nature itself, but nature exposed to our method of inquiry."

Scientific inquiry happened all over the world, and ancient India, or Bharat, was no exception. In fact, Bharatiya science had made great, pioneering strides in many different fields. Today, thanks to more than a thousand years of relentless assault on this civilisation, much of this science is lost or greatly appropriated. Today, when we talk of Bharatiya thought, we either refer to its popular culture like its festivals, costumes, rituals, food, etc. or to its spirituality and its different existential philosophies. These two ends of the society, were kept together by different forms of "Vigyan" or science, that addressed practical questions of everyday interest.

Much of the hermeneutic elements of Bharatiya Vigyan, are given distorted meanings and religious colouring, thanks to flawed interpretations by scholars from occupying powers. For instance, the term dharma is variously interpreted as "religion," "ethics," "duty," "divine law," and so on. The term karma has come to mean some form of divine retribution. The term atma is called "soul" and the term vidhi is called "fate," and so on.

All of these are incorrect interpretations, resulting due to a method of interpretation called "Syncretism" that draws parallels between terms from an alien culture, to terms from one's own culture. It is only in recent times. that there is an increasing realisation that the world's understanding of Indian thought is highly distorted. And we have seen several efforts to spread greater awareness and perform some corrective action. The book Sanskrit Non-translatables by Rajiv Malhotra is one such effort.

"Digesting" terms from an existing hermeneutic framework into an existing framework, delivers a death blow to the knowledge and wisdom latent in the framework. But today's science, driven largely on machine hermeneutics is so powerful and dominant, that presenting anything from a different method of inquiry is deemed unscientific.

*~*~*~*~*~*

For those of us who were brought up in the Western paradigm of science (which includes most, if not all readers of this post), there is a need to represent the hermeneutic basis of Indian science Bharatiya Vigyan ("Indian science" perhaps refers to Western paradigms of science practiced in India, today).

Here is an attempt towards this.

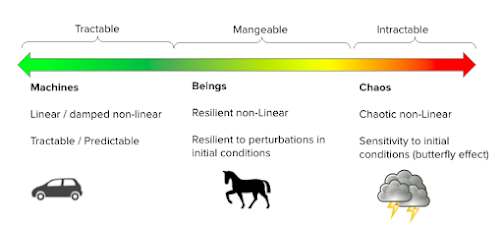

However, the transition between linear and chaotic non-linear systems is not abrupt. In between linear and chaotic non-linear systems are a class of non-linear, complex systems, that display properties of not sensitivity, but stability and resilience to initial conditions. Let us call this class of systems as "beings." All living beings are "beings" but several "non-living" systems are also complex and resilient, satisfying the definition of a being. The term jivatma (that. is sometimes translated as "materialized soul") is nothing but a complex, resilient system or a "being" as far as a Bharatiya scientist is concerned.

Bharatiya Vigyan started understanding the universe, by representing it using "beings" rather than "matter" as we do today. The primary characteristic of a "being" is to "be" in a "state of being." Any minor perturbations would bring the being back to its stable state. The states of being that "hold" or are resilient or "sustainable" are called its dharma. Every being has its own dharma or its own resilient state of being. It is so ironic that this term today means "religion" or "duty" when it is actually a systemic property of physics!

Any stable state of being of a complex system has its own energy and information content. This gives the being certain "capabilities" which is called prana. It is ironic again that we now associate the term prana with a narrow definition of breath.

While all living beings are "beings" just about everything else can also be modelled as a being. Molecular structures that form solids are in a stable state of being. If they are perturbed a bit, they return back to their original form (which we call, "elasticity" in physics). Similarly atoms are in a stable state of being, with protons and electrons balancing out one another. If an atom loses an electron, it loses its dharma and becomes an unstable ion, leading to static electricity, lightning, and so on.

Bharatiya scientists understood that just about all of life is a state of dharma. Our entire ecology is but a complex, resilient system, with its own stable states of being. The ecosystem hence, has its own dharma. And why just ecology? Even the solar system and perhaps the entire universe is nothing but a being. What appears chaotic (like say, thunderstorms) may just be a small part of a larger, resilient system of being (like the climate).

While a stable state of being sustains for a while, we can also see that nothing in the physical world sustains forever. Life sustains for a while and dies away. Seasons sustain for a while, and change. Societies sustain for a while, and gets into turmoil. Even stars sustain for a (long) while and collapse. Even objects of the mind, like cultural practices, languages, and so on, do not sustain forever. Bharatiya philosophers hence started asking, what entity if any, sustains forever? The Sanskrit term for "forever" or "eternal" is Sanatana. The search for eternal sustainability came to be known as Sanatana dharma. This is what the "religion" of "Hinduism" is called in India.

The notion of "religion" for the Bharatiya mind, is very different from what is conventionally understood as religion, in the West. It is not about commandments, nor about belief, nor about faith, nor about prophets and holy books. It is also not about rituals, norms, and specific forms of cultural practices. At its core, the practice of Sanatana dharma is about inquiry, search, conceptualisation, model building, hypothesis testing, argumentation, debate, and so on. Pretty much the stuff that "Science" is made of today.

If we have to revive Bharatiya Vigyan, we should recover terms like dharma, karma, vidhi, etc. that have been give religious connotations, and provide them proper definitions using systems science.

05 November, 2021

Yoga psychology - 3: Consciousness and Witness

In the third post in this series on Yoga Psychology, let us visit some of the core concepts of our sense of self and understand some of its nuances. The concepts presented here are not directly from Yoga Sutras. They stem from Vedanta, which in turn form the basis for the psychology of Yoga.

In the first post in this series, we saw how our "sense of self" as an entity is different from our body, thoughts, emotions, and even our hard-coded genetic "nature". We can talk about all of them as if they were objects of inquiry while we, or our "self", is the inquirer.

One of the postulates of Vedanta is that our sense of "Self" can never be the object of inquiry. It is always the inquirer. Just like the eyes can't see themselves, the "Self" cannot see itself. Our eyes can however, see an image of themselves (say in a mirror or a photograph) and realise that this image represents the very eyes which are doing the seeing.

Similarly, we cannot "see" our self-- but we can become "conscious" of its existence. We become conscious of our self when we detach our sense of self from our body, mind, thoughts, emotions, nature, etc.

Earlier, we also said that the universe is but an all-pervading consciousness. But now we are saying that the consciousness is not our "self" itself. Consciousness can make us aware of something. It is consciousness that makes us aware of objects in our vicinity. When consciousness is focused on some element of our surroundings, to the exclusion of others, it is called attention. When we become conscious of our thoughts, we enter into a state of meta-cognition, which helps us become aware of our own thinking. When we become conscious of our emotions, we become "mindful" and aware of how we are being driven by our emotions.

In Vedanta, consciousness and our sense of self are distinguished from one another. Consciousness is called chitta, while the self is called the "witness" or sakshi. When we become aware of our "witness" we are indeed our own witness. Hence the witness cannot inquire about itself directly as it inquires about the world outside. It has to inquire about itself indirectly-- via our consciousness or chitta. The self needs to "project" some part of itself on the consciousness and witness the reflection it creates in the consciousness.

Because of this, our reflection in our consciousness needs to be "clear". It cannot be smudged by our emotions, thoughts and delusions. A large part of Yoga psychology is geared towards how to make our consciousness clear, so that our self can reflect itself.

*~*~*~*~*

We now turn to other nuanced differences between Vedantic models and how modern science views these concepts.

In modern science, consciousness is seen as something that emerges from the physical interactions of neurons in the brain. In contrast, in the Vedantic models, our brain (and body) can only "tune" into consciousness that is already all pervasive. Consciousness that lead to present-day science and mathematics existed during the time of dinosaurs too-- except that their brains couldn't tune into it. Consciousness exists on Mars and Jupiter too-- except, no physical device exists that can tune into it there and make an impact. We don't "invent" mathematics we "discover" mathematics from the consciousness that is already there. Any machinery that can discover mathematical truths on Earth, can also discover these truths on Mars or Jupiter, if it can only physically sustain itself.

Hence, according to Vedanta, conscious AI (or what might be termed AGI or Artificial General Intelligence) is very much possible-- if only we can figure out the logic for tuning into the all-pervasive consciousness.

Because in modern science, consciousness is seen as an emergent property of neural interactions, it is considered that when we are in deep sleep, we have no consciousness. This is another point where Vedanta differs from modern science. In Vedantic models, when we are in deep sleep, we have no witness, but all we have is consciousness. Even in deep sleep, our body and mind are kept alive by our consciousness-- but because there is no one to "witness" it, there is "no one" to be aware of what is happening.

The "witness" is so important to our existence that, without the witness, our consciousness cannot take decisions and keep us functioning for long. If the "witness" is away for too long, we may never wake up from our sleep.

Samkhya philosophy of Vedanta proposes a complete model of universal reality based on this duality between consciousness and witness. It is called Prakriti and Purusha. Prakriti refers to existential reality of the physical universe that functions by the laws of physics. Purusha refers to the eternal reality of the universal Self or universal truths whose presence is critical for Prakriti to keep functioning.

*~*~*~*~*~*

Coming back to Yoga psychology-- we had earlier noted that Yoga means "to unite" or "forge" or "harmonize". The ultimate goal of Yoga is to harmonise our consciousness with our witness. Our consciousness is our driving force, while the witness is our driver. Our driving force is very powerful and autonomous-- in other words, it is an extremely advanced form of machinery-- not seen so far in the machines that we have built. And as is with any advanced machinery, configuring it to function properly (in this case, to harmonise with the witness) is not an easy job.

Hence, the need for a complete philosophy of Yoga.

21 October, 2021

Yoga psychology - 2: Gunas

In the previous post in this series, we saw how our "sense of self" is different from our body, thought, emotions, and even our hard-coded emotional disposition. We can separate ourselves from all of them and inquire about them as if they were separate objects.

We also introduced the model of universal consciousness that is central to Indian thought, and that our self is very much this all-pervasive universal consciousness.

We also talked about "identity" and how our existential self (somewhat analogous to the "Ego" of Freudian model), called our "jivatma" has a lot of energy and cannot but identify with something or the other. A "enlightened" person would hence, manage this energy and carefully curate the set of identity objects to which it would attach to.

In this post, we will talk about the "states of being" of our existential self and what does it take to curate its identity.

The Mandukya upanishad talks about the story of "two golden birds perched on the self-same tree". It starts thus:

A deluded jivatma fights its tethers and wants "freedom" from its own inseparable companion. But an "enlightened" jivatma does not consider this a state of bondage, to be tethered to the universal self-- instead, it realizes that all its awareness comes from the universal self, and actively seeks its guidance to engage with the world outside.

*~*~*~*~*

The jivatma may be deluded because it is in a "state of being" where it is unable to listen to or tune into the universal self. Swami Vivekananda gives the analogy of a lake at the base of which, lies a precious gem. But often, the waters of the lake are turbulent, or turbid, which masks our view of the gem residing underneath. It is only when the waters are calm and clear, is the gem visible.

The turbulence and turbidity in the lake refers to the state of being of the jivatma. Broadly our individual self can be in three different classes or states of being, which are called: tamas, rajas and sattva respectively. These are called our gunas.

Before we explain the gunas, let us connect them with analogous concepts from Cognitive Science, so we can understand them better. Cognitive Science today, classifies our emotional state into two broad classes based on their "arity". These are the so-called "negative" and "positive" emotions respectively.

An emotional state is a "psychosomatic characterization" of our being. What this means is that an emotional state, "primes" our body and mind, for a specific class of responses. The same stimulus can elicit different kinds of responses, based on the emotional state that we are in.

For instance, suppose we are in a state of fear after seeing some dreadful news trend on social media, and we are walking alone in the darkness. A stranger suddenly starts approaching us. Our immediate response would be driven by this fear, and prompt us to avoid, flee or make ourselves defensive. On the other hand, suppose we are walking alone in the darkness after we come out from a party and celebration, where we had a great time with friends. In this case, we are much less likely to feel threatened by a stranger approaching us, and would more likely believe that the stranger is lost and may be asking for directions, or some such.

"Negative" emotions like fear, sadness, anger, etc. primes our body and mind to disengage from the world, while "positive" emotions like joy, pleasure, happiness, etc. primes our body to engage with the world. In a negative state of mind, we build defenses, we disengage, we are distrustful, we avoid interactions, we are stingy, we are risk averse, and so on. While in a positive state of mind, we are proactive, generous, trustful, assertive, willing to take risks, and so on.

*~*~*~*~*

The state of tamas pertains to a state of being where we seek to disengage from the world. It is characterized by lethargy, lack of motivation, sluggish behavior and so on. The state of rajas seeks to actively engage with the external world. In a rajasic state, we are assertive, expressive, feel entitled, full of energy, and so on. As we can see, the tamasic and rajasic states roughly correspond to negative and positive emotional states, respectively.

The sattvic state of being is where the mind is optimally tuned to awareness. It seeks to neither disengage from the world, nor to proactively engage with it. A sattvic state is where one is guided by awareness, rather than by emotion.

Often, we come across moral posturing that calls sattvic state of being as "higher" and rajas as tamas as lower down in some of a cosmic, spirit hierarchy. This kind of moral posturing, in my opinion, only makes our mind's lake turbid and takes us away from really understanding these gunas. The moment something is regarded "holier" than something else, we get questions like, why did "God" create the less holy things, and so on.

Note the copious absence of terms like "God", "Almighty", or any discourses on morality from the description of Yoga psychology. We are talking about consciousness, and positing that consciousness is something that is beyond our body, mind and emotions-- including intuition. This is a very specific postulate that forms the core of Indian worldview-- that there exists a universal consciousness that is the universe, and that is what gives us our sense of awareness. And that the core of our self is this universal consciousness that unbounded and eternal.

Someone who claims to be in a sattvic state of mind all the time is either fully enlightened (in which case, others would be saying this about them-- not they themselves), or is telling a lie. A sattvic state of mind is very resource intensive. To be acutely aware and direct that awareness at will, requires a lot of energy and control. This is where the other states of being become important.

A tamasic state of being is what we would typically experience on a lazy weekend. We need this "laziness" to recharge ourselves and bring some succor. This is when our mind and body relaxes, and our long-term (or subconscious) memory takes over and processes all that we have experienced. We need the tamasic state to prevent ourselves from burning out, and learn from our experiences. Disengagement from the world, is a fundamental survival instinct. Nothing "less holy" about it.

Similarly, we need passion, drive and gumption to make an impact in the world outside. All these are part of the rajas guna. We need the rajas to bring enthusiasm and joy, and the drive to make things happen.

However, tamas and rajas that are not guided by awareness, can get into an uncontrollable intensity, where they take our mind into a state of trauma. An uncontrolled tamasic state where we cannot come out of our urge to disengage from the world, leads to depression, suicidal thoughts, anger, frustration, and so on. Similarly, an uncontrolled rajasic state where we cannot control our urges to express and experience, leads to indulgence, lack of empathy, addiction, vice, and even psychopathic behavior.

One who is guided by awareness, knows how much and when to engage and disengage with the world. Both tamasic and rajasic states of being are important aspects of our being-- and their optimal orchestration comes from a sattvic state of being.

17 October, 2021

Yoga Psychology - 1: Self and unity

Over the last several years, I have had a growing interest in Cognitive Science and models of the mind. A chance encounter with some learned scholars, lead me to rediscovering the roots of Indian thought through a completely different hermeneutic framework from the machine hermeneutics that we study in school. I have documented my thoughts in several different ways-- Facebook posts, a series of posts on this blog with the label "Theory of Being", and a self-published Kindle book by the same name. My dream is to recreate a full-fledged theory of complex systems based on the theory of "being" with tools and methodologies to implement them in practice.

More recently, I stumbled onto the theory of Yoga-- a practice spanning over several centuries, and which was documented and formalised by Maharshi Patanjali who is thought to have lived sometime between 7th to 2nd century BCE. This post is part of a series on my understanding of the human psyche based on the theory of Yoga.

We start this series with the first post trying to understand the core of our existence through Yoga psychology.

One of the fundamental things that Yoga psychology teaches us is that our body, mind, emotions, including our emotional dispositions hard-coded in our genes, are objective to our existence. We can separate them from our "self" and inquire into them as if it were an independent object. We can talk about our body as if it is something different from us; we can talk about our thoughts, beliefs and even prejudices as if they were different from us; we can even engage with our emotional dispositions and for example, say things like, "I am nervous by nature, and know why this is hard-coded into me and what evolution is trying to tell me, and I have also learned how to manage this nervousness"-- going on to show that, "my nervous nature" is something different from "me."

Ordinarily, we "identify" with a lot of things-- including our body, thoughts, emotions, etc. This means that our "self" attaches itself to these objects, and acts as if it were these objects. When we identify with our body, we act as if we are our bodies. When we identify with our thoughts, we act as if we are our thoughts. Hence, when someone strongly identifies with an idea, like say, their gender, their nationality, their race, their ethnicity, etc. they act as if they are that object. Any reference by anyone to that object, is construed as a reference to them. Hence for example, if someone strongly identifies with their assigned gender, and say someone else rejects a gendered approach to life, it is construed as a rejection of their person. People with a strong sense of identity, actively work for the interest of their object of identity, expend time, energy and other costs to defend it from perceived threats, and do not ask what benefit they are getting from this association.

Identifying with something is hence, fundamentally different from rational association. Rational associations are based on expected benefit versus cost. But identity is something that is beyond considerations of benefit and cost. We are what we identify with.

Much of the upheavals-- both positive breakthroughs and human-induced disasters, in the world have been due to some core set of people strongly identifying with an idea. The passionate curiosity of Marie Curie led to the discovery of Radium and also radio-activity, when her discovery ultimately ended up killing her. Similarly, it is the passionate bigot who "becomes" her/his prejudice that create enormous conflict and crises.

Curating our identity is hence a very fundamental and deeply important activity. We have a lot of "self-energy" (if there is such a term) within us, and we cannot but identify with something or the other, through our lives. We need to be very careful in choosing what we identify with-- what is that idea that we let become a part of who we are. Because, this is going to have irreversible consequences.

The psychology of Yoga tells us something very deeply profound-- that our "self" is different from all the ideas and emotions that we possess, as well as our physical bodies. Yoga sutras teach us to objectively inquire into our body, thoughts and emotion by first disassociating from all of them.

So, if we are not our body, nor our thoughts, nor our emotions, and not even our "nature", who are we then? What is this "self" that is us? If we de-identify from everything-- from our bodies, our thoughts, our families, our countries, our genders, our communities-- what remains? Who are we?

Indian thought has long since asked this question-- who or what is this "self" that is attaching itself to objects and driving our lives? The Upanishads in particular have long debates and discussions about the nature of our selves.

Indian thought has long since maintained that the core essence of the universe is an all pervasive "consciousness" or "awareness" and our "self" is very much this indivisible, core, awareness that pervades-- or "is"-- the universe.

The hermeneutics of machines that drives the study of modern physics, has no place for "consciousness"-- a term that is relegated to "mysticism" or "pseudo science" primarily because we cannot "see" or characterise it. However, science does work with several elements that we cannot "see" or "perceive"-- like radio waves, magnetism etc, and infer their existence and properties from how they affect the world outside.

The term "Yoga" means "to unite" or "to synchronise" or "to harmonise" our existential elements like our body, mind and emotions with the all-pervasive consciousness. The major impediment to bring about this unity is actually our sense of agency or "free will". A deluded free-will or a will that is trapped in its thoughts and emotions, and strongly identifies with something or the other, is as much of an impediment to bringing about this unity, as an "enlightened" free-will is a catalyst to bring about this unity.

30 November, 2020

Dharma and Ergodicity

In the last couple of years, I have spent a lot of time trying to interpret the notion of dharma and traditional Indian worldview using systems theory. You can check out older posts with the label "Theory of Being" and also my book on Amazon called "Theory of Being".

In this post, I put forth some more working ideas towards building a more comprehensive theory of systems using Indian thought. The ideas presented here are work in progress-- meant to provoke thought and get feedback. Ideas presented in this blog are subject to future revisions as I get more clarity.

*~*~*~*~*~*

When we study systems we are first taught that a system is an ensemble of interacting parts. The interaction between the parts or the system dynamics, is what characterises a system-- without which, it would just be a collection of different parts, and not a system.

Systems are everywhere-- in fact, a non-system is much harder to find and/or create, than a system. Even an inanimate piece of matter, like a stone, is a system of tightly interconnected molecules interacting in specific patterns that keep the solid matter intact.

When we study systems in today's world, we are taught about two kinds of systems called as: linear and non-linear systems. The latter is also sometimes called "complex" systems.

Linear systems are so called because their dynamics can be represented in the form of linear differential equations. In an intuitive sense, they represent an "open loop" interaction with their environment where inputs from the environment and the outputs to the environment do not confound one another.

Almost all machines adopt a linear design model. Even with complex machinery like say an airplane, the overall flight dynamics is still linear. What this means is that the input that goes into the airplane (the air in front of the engines) is separate from the output (or the exhaust) that comes from the airplane. Airplanes in their current design would find it very hard to fly, if the exhaust and the turbulence it creates, were to somehow come back to the front of the engine. Indeed, when planes fly too close behind other large airplanes, they are known to even crash from the exhaust turbulence, also called the wake turbulence.

But most natural systems are non-linear in nature. Human societies, ecosystems, weather, etc. all display rich forms of "closed-loop" interactions where the output of some unit in the system comes back to affect it subsequently. We see that in human societies all the time. Our output or actions have consequences that can come back to haunt us, in the (wrongly) called "law of karma".

Non-linear systems are known to be very hard to model, understand and predict. The term "butterfly effect" comes from the study of non-linear systems, representing what is called "sensitivity to initial conditions"-- which means that a small change in the initial conditions of a non-linear model, can result in vastly different ways in which its dynamics would pan out over time. Colloquially, it is said that, a butterfly flapping its wings in one part of the world, can potentially create a chain of events causing thunderstorms in some other part of the world.

While non-linear systems are hard to model and understand, not all non-linear systems pose a hopeless case. Ludwig von Boltzmannn, who was one of the pioneers in statistical mechanics-- or the study of large number of interacting entities using statistical techniques, had this hypothesis about complex systems: large systems of interacting particles settle down to a stable state where the time average along a single trajectory equals the ensemble average.

This hypothesis was later found to be false, and not applicable universally. But it was true of a specific class of interacting, non-linear systems that has now come to be called "ergodic" systems and the above hypothesis is now called the Ergodic Hypothesis.

To understand ergodicity, let us take an example. Consider a music troupe-- my favourite is ABBA-- (I know, I am old!) who are famous and have a large fan following. They are known for their superlative performance that draws a huge audience whenever they perform. But each time they sing, their performance would not be an exact replica of previous performances. The same song sung at different times would be a little different from one another. But this difference will not be arbitrary-- most of the performances would hover around an expected set of metrics about music quality, beats, emotions, etc. that have made them famous. It would hardly ever be the case that the first time they sing a given song, it would be sublime and the next time it would be downright jarring.

Suppose, in order to "quantify" ABBA's performance, we develop a set of metrics like highest musical pitch, number of frenzied fans, number of beats per minute, and so on, and we measure them painstakingly across each of their songs. Now, we can see the ergodic property that in a single long performance, the average of these metrics would likely be the same as the average of these metrics obtained from a large number of independent concerts. In other words, to get a good idea of an ABBA performance, we could either take small samples from several of their performances, or sit long enough in a single performance. In both cases, we would get a pretty good idea of an ABBA performance.