Indian thought has been greatly shaped by the philosophy of Vedas that are estimated to have developed over several millennia, beginning as early as 22000 BCE.

The Vedas presented a deep, abstract model of reality, that has in turn shaped collective worldview and notions of religion, ethics, morality and science. The civilisation formed under the influence of this philosophy (even those subcultures that rejected this philosophy) was vibrant and diverse, with different schools of interpretations appearing throughout history. There were also several periods of stagnation and degeneration, followed by rejuvenation of this philosophy by one or more social reformers, including Buddha, Mahavira, Adi Shankara, and so on.

In this post, we address one such issue that has created deep roots in Indian thought, and which is in dire need for reforms.

*~*~*~*~*

The core inquiry of Vedic thought focuses on the nature of our self. The Upanishads, which are considered the essence of the Vedas, have several models and analogies to help us understand who is this "I" when we refer to ourselves.

We can see that we as the observer or the subject, is separate from the observed, or the object. And when we start observing ourselves, just about everything we thought represented us, becomes an object of our observation-- meaning that none of these define our "self." We can separate "us" from our thoughts, our emotions, our innate nature, our desires, our delusions, and so on. Our self is none of these. We are not our thoughts, we are not our emotions, we are not our innate nature, since we can observe all of them objectively.

The only entity we cannot observe is our "self" itself. This core entity which is our true self, is called the "witness" or Sakshi, who observes everything. We cannot observe our witness-- if we are observing our witness, then who is the witness witnessing it? We can only "become" our witness.

The sense of self that we normally project as part of our daily lives is known as the "jivatma" or "ahamkara", which is somewhat equivalent to the concept of ego in Freudian thought. The only way our self observes itself is by looking at its reflection, which is the ahamkara. It is somewhat like how the only way our eyes can see itself is by looking at its reflection in a mirror.

What is the medium that is giving this reflection? This is postulated as our mind. Our mind is the medium which hosts the reflection of our true selves, which appears in the form of our ego.

The reflecting surface may be imperfect. A mirror may be stained, dusty or even broken. The reflecting surface affects the reflection. Our reflection in the mirror may appear dull or stained or broken-- but it is only our reflection. Our true self, which lies beyond the mirror is unaffected by all the thoughts, emotions and innate nature that shape the medium of our mind.

*~*~*~*~*

A major debate among Vedic philosophers has been to model the association between our real self and the reflected self and its medium. Is our real self completely independent of our manifested self? Just like how we are completely independent of any mirror that reflects us? Or is there some "binding" that binds our real self to the mind/body medium that is reflecting us? Is there some reason why our real self is strongly associated with-- or even "trapped" in-- the mind-body complex that is reflecting it?

In the 10th century CE, Vedic thought went through one more round of major rejuvenation, by the works of Adi Shankara from present day Kerala. In his quest to revive Vedic philosophy, Adi Shankara wrote detailed commentaries on 10 Upanishads that are now called the "principal" Upanishads, and formulated his own school of thought called Advaita Vedanta.

According to Advaita which literally means "non-dualism", everything in the universe is made of the universal consciousness that is called Brahman. That includes our witness, our mind, our ego, our body-- everything. There is hence no difference between us and the mirror. Imagine that our hands were to be a reflecting surface, and we put up our hands to get a reflection of ourselves. We may not be our reflection in our hand-- but we are very much the hand and the reflection as well!

Other philosophers like Madhvacharya disagreed with this interpretation by arguing that it seems to border on nihilism. If everything is the universal consciousness Brahman, and there is no semantics associated with our existential self, then why do we have notions like ethics, morality, duty, principles, and so on? A similar argument was also given more than 1500 years before Madhvacharya, by Siddharta Gautama (Buddha) who was disillusioned with a puritanical notion of "everything is Brahman" leading to nihilistic thought.

One of the theories that came about to explain the relationship between our true self and the existential self, is the concept of prarabdha karma. The term karma means "action" but thanks to this theory, karma has now come to mean "retribution" in popular thought.

The idea of prarabdha karma is that our existential self goes through several cycles of births and deaths, and the karma (actions) it performs out of its own free will in one life, has consequences and gains some baggage, which becomes our prarabdha (starting) karma as we begin our next life.

The idea here had been to provide a sense of accountability for people acting out their worldly desires, by saying that their actions will have consequences and they will need to own up their actions. This is somewhat similar to the notion of judgement day in Abrahamic religions. But in contrast to being "judged" by a third party, we get to suffer or enjoy the consequences of our karma in our next life.

While this looks like a neat theory and strategy for bringing about accountability, this theory also has a dark side. The idea of prarabdha karma and "next life" can also ironically make people very apathetic towards one another. If someone were to be born with some birth defect, then not only they have to live with their birth defect, but they are also insinuated by others, that they must have done something bad in their previous life, and so are suffering in this life! Not only do they not get support and empathy from others, they have to suffer an unknown guilt all their life!!

And of course, this leads to feudal hierarchies like "lower" births and "higher" births based on what one had done in their previous life.

*~*~*~*~*

The above notion is in serious need of reform in today's world. Firstly, there is no evidence for any past life of any kind. Indeed, if we only go from life to life, then the total amount of living beings on earth needs to be constant! If everyone is born with a baggage from their previous life, how come we have more people today than there were a century ago?

In fact, we have a much better explanation for where our innate nature comes from. It comes from our genes!

If we have to understand our innate nature, we don't have to look for some non-existent "past life." We just have to look at our genetic ancestry. We know for a fact that, intense experiences like desperation and trauma encountered by one generation, makes its genetic imprint on the next generation. The next generation is innately equipped with defences and barriers to avoid what the previous generations went through.

Social accountability is an important question-- but that it should not be confounded with our innate genetic nature. There is no reason to equate our innate nature with some form of undesirable actions we are said to have performed in some fictitious past life.

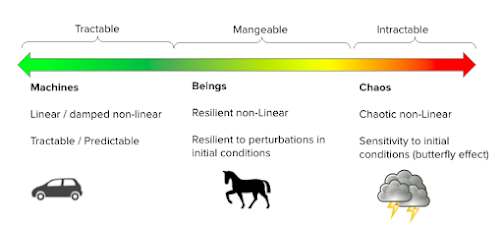

It is time we replaced prarabdha karma with prarabhda guna (initial characteristics) and separate it from the actions we do in this life. I have written separately about karmaphala or the consequences of our actions. It is an profound theory in itself, that can be understood better when we understand the dynamics of complex systems. The consequences of our actions have nothing to do with our innate nature, which is just an accident of birth.